[The image promoting the exhibition is a collage by Magdalena Sobolska. It is maintained in brown and blue tones. In the foreground there is a pond in which divers are immersed. A black hand with golden fingertips, from which a lily is growing, emerges from the water. To the right of the painting sits a smiling girl with no legs, dressed only in a T-shirt and panties. On the left are pasted naked male bodies. One of them has no leg and his hands are sticking out from under the amputation at the level of the thigh. They belong to the other figure, which is able-bodied, leaning forward to provide support for the legless person. In the background are visible rocks, stones, desert sand, bushes, and behind them a rocky mountain].

Participants: Pamela Bożek, Bojka Diving Collective, Daniel Kotowski, Nowolipie Group, Paulina Pankiewicz & Grzegorz Powałka, Joanna Pawlik, Rafał Urbacki, Karolina Wiktor, Liliana Zeic, Katarzyna Żeglicka, Artur Żmijewski.

Assistance: Zofia nierodzińska

Arrangement: Raman Tratsiuk

Visual identity: Magdalena Sobolska

Promotion: Ewelina Muraszkiewicz

Coordination of events: Joanna Tekla Woźniak, Kinga Mistrzak

Editors: Bogna Błażewicz, Jacek Zwierzyński

Translations into language easy-to-read and understand: Agnieszka Wojciechowska – Sej

Translation into Polish Sign Language: Marta Jaroń, Anna Borycka, Kamila Skalska, Karolina Bocian

Audio descriptions: Remigiusz Koziński

Translation into English: Marcin Turski, Zofia nierodzińska

Proofreading: Richard Pettifer

Production: Marcin Krzyżaniak, Yuliya Zalozna, Viktoria Zalozna, Zbigniew Wanecki, Szymon Adamczak, Monika Petryczko, Krystian Piotr, Michał Mądroszyk

Collaboration: Zofia Wiewiorowska

Disability can be an identity a person assumes, a condition they struggle with, a space where they find freedom, or a concept that is used to marginalise and oppress. It can also be all of these things at once.

Sunaura Taylor

In disability studies, a distinction is made between impairment and disability. Impairment refers to physicality–the (in)capacities inherent in the body we inhabit – while disability is a social condition related to cultural perceptions of people with disabilities, and the degree of accessibility existing in shared spaces. The former is a medical category, the latter a political one. The society that makes people disabled heats up debates, and mobilises activists’ fights. In Poland, the most notable event in the history of the struggle for a dignified life for people with disabilities remains the 40-day occupation of the Sejm building in 2017. The play A Revolution That Never Happened, performed by actors of Theatre 21, was based on this event.

Sunaura Taylor, author of Beasts of Burden[1], published this year in Polish, expands the concept of disability and impairment to include the environmental category. She writes and talks about the liberation of people and other animals from the yoke of ableism, which she links to the Anthropocene. She uses the term “disabled ecologies” to describe places destroyed by extractive human activity. Humans influence the environment, and the environment causes illness in inhabitants of industrialised areas by, for example, drinking contaminated water. Following Donna Haraway and Anna Tsing, instead of leaving polluted areas and colonising more planets in the Solar System, the author calls for “staying with the trouble”, i.e. taking responsibility for the history of capitalist accumulation and the effects of racialised policies, the effects of which are felt the most by indigenous people in the Americas and the Global South. As someone living with arthrogryposis, or congenital joint stiffness, she identifies with the ‘damaged landscapes’ in which she grew up.

In the documentary Examined Life–made by her sister Astra Taylor–Sunaura goes for a walk with the well-known gender theorist Judith Butler. One body moves in a wheelchair, the other needs shoes to comfortably traverse city pavements and streets. Both deviate from what late-capitalist society calls “the norm”. The queer and crip bodies confront architectural space, are immersed in a social context, and analyse their positioning using philosophical concepts and their own experience. Sunaura talks about drinking coffee from a paper cup using only her mouth–her hands are paralysed–and about the discomfort this causes to other people in the café. Judith replies that for her it is a story of dependence, about whether we as a society are ready to assist and support each other. Their conversation blurs the boundaries between the able-bodied–defined as radically independent–and the disabled, that is, the dependent, between what is considered feminine and masculine, between what is called human and what is called animal. The philosophers move through one of the most accessible places in the world, namely the streets of San Francisco.

In 1950s Warsaw, Jadwiga Stańczakowa, a writer and journalist of Jewish origin, loses her sight. She describes her experiences in her book The Blind [Ślepak], which she records on a tape. She writes down the recordings using a typewriter with individual letters marked with a piece of plasticine. Stańczakowa knows that her experience is unique, that the process of losing her sight and writing from under her eyelids can be told only by someone like her, a blind person, a “ślepak”. Her initial limitation becomes an opportunity for her to broaden her experience beyond ocularcentrism; in the book, she refers to sighted people as “sighters [wzrokowcy]”. To get out of her flat she needs a network of people supporting her. As a woman in a patriarchal society, in spite of her disability, she is used by her fellow poets to perform daily chores they don’t want to complete–for example, Miron Białoszewski, to whom she returns the favour of a creative conversation by washing his socks.

Disability is therefore an intersectional category, bringing together the various exclusions to which non-normative bodies are subjected. Recognising and accepting otherness allows us to challenge the dominant narrative based on the depreciation of the experience of people with disabilities, points out the oppressiveness of commonly-used categories, and enables us to imagine other, more equal and non-stigmatising rules. Thus, disability, alongside ethnicity, gender, class and species, becomes another possible category of emancipation. However, emancipation here is not measured by the degree of independence and autonomy, but, on the contrary, by the ability to form alliances, support, and take responsibility for each other.

The exhibition Politics of (In)accessibility, Citizens with Disabilities and Their Allies brings together different experiences and perspectives on the issue of disability. It takes a look at already historical works, such as the series of photographs An Eye for an Eye by Artur Żmijewski, a representative of critical art. In photographs taken in 1998, bodies are depicted: amputees and abled ones, complementing each other to create hybrids and mutants, creatures with five legs and two heads. The photographer takes a distanced position, the author looks at his “objects”, and animates them into taking poses. He is a collector of extraordinary bodies[2]. He wants to break the taboo of invisibility of people with disabilities in the public sphere, but he does not allow them to speak. The figures in his photographs are oddities put on display, as in the infamous freak shows[3] popular in the 1930s.

The prematurely-deceased dancer and choreographer Rafał Urbacki in his performance Mt 9,7 [And he arose, and departed to his house] speaks about disability from an autobiographical perspective. The artist confronts his religiosity, his affiliation to the Catholic Church from which he left–or rather, which excluded him when he realised his homosexuality. In a 20-minute performance, we learn about the story of acceptance and rejection, the search for identity and the resistance that an impaired body puts up to limitations, both from society and of its own. The adult Rafał gets up from his wheelchair, not by a miracle, but thanks to exercises and a movement method he has developed himself. The enormous effort he makes, however, does not stop the chronic disease. Rafał dies as a result of myopathy in 2019.

At the opening of the exhibition, activist and dancer Katarzyna Żeglicka will present an autobiographical performance entitled Contrast Resonance, in which she revisits a memory associated with the oppression of medicalisation. Katarzyna describes herself as genderqueer and crip. Through her work, she “spits ableism in the face”. She considers dance a form of activism and emancipation. During the exhibition Katarzyna will organise a workshop “Move over!” about transforming inaccessible spaces.

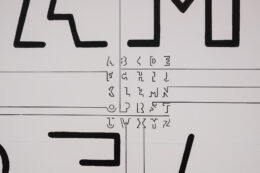

Karolina Wiktor is an Aphasian, i.e. a person who has lost the ability to use language, the ability to speak, read, and write. Her aphasia was caused by a stroke she suffered at a very young age. For the ex-performer, the disease and the resulting loss of memory became the subject of her art, while art itself became a practice of self-healing. At the exhibition, Karolina will show an installation entitled SAMOREAL based on a language system she created herself, which she calls “The Alphabet of the Missing Font”. The alphabet has been constructed in order to learn again the codes of communication with the world. As the artist herself says in an interview with dwutygodnik:

“I constructed the alphabet inspired by the word ‘lack’, and the new wave music band of the same name, which used a brutal red font from which elements of letters were cut out.”[4]

Liliana Zeic describes herself as an ally, or rather one who is still learning allyship. As an able-bodied, white, queer, cisgender woman, she based her presence in an exhibition about (in)accessibilities on the bodily experience of trauma. She emphasises the relational nature of dealing with difficult experiences, and visualises them through a graphic sign and an object.

Joanna Pawlik’s large-format photograph Untitled (Magda) shows a smiling young girl with no leg sitting on a bed. What draws attention is the easiness with which the model poses for the photograph, her unpretentiousness and undisguised joy.

Paulina Pankiewicz is an artist and a runner. She has been guiding long distance blind runners for 10 years. She is an ally. The installation Psychogeographic Views, created in collaboration with athlete and massage therapist Grzegorz Powałka (now deceased), is a record of their walks–an urban drift [dérive] inspired by Situationists’ practice. While Grzegorz describes space with words, Paulina chooses drawing. The overlapping of these perspectives–of a blind person and a sighted one–results in a very subjective map of the city, which shows places that evoked particular feelings in the authors. Running is also an auditory inspiration for Paulina. An ‘opera’ composed of runners’ breath will be staged during the opening.

The Nowolipie Group is a phenomenon in the Polish art field. It was formed in 2005 as a result of the alteration of a ceramic workshops for people with disabilities, run by Paweł Althamer. In practice, he extended Joseph Beuys’ maxim, following the principle: “everyone can be an artist, some people simply need to be assisted”. The group combines the pleasure of spending time together with the creative process, which usually materialises in the form of a concrete work: a painting, a drawing, or a sculpture. At the exhibition in the Arsenał Gallery, Nowolipie will present the painting Still Life and organise workshops, to which they invite everyone regardless of age and (dis)ability status to draw with them.

Pamela Bożek’s self-portrait with her son Not All Gold and the accompanying object–a golden plaster–are a record of the way in which the experience of a child’s disability is dealt with in a public space. As the artist writes: “A desperate and extravagant strategy of aestheticisation–the gilding of post-operative plaster bandages–turned out to be an effective protection against difficult, mass expressions of sympathy, surprise, and curiosity, which prevented even a momentary escape from pain and discomfort.”

The Bojka Diving Collective brings together female divers with varying abilities and health status, who are often also at risk of economic exclusion. Bojka’s activities include counteracting gender discrimination (mainly against the marginalisation of women in the diving community), fight for the aquatic environment (with a particular focus on coral reefs) and using diving as a tool for emancipation. During the exhibition, the collective will show a series of posters relating to the (in)accessibility of institutions and urban spaces for people with disabilities.

The exhibition is a place where different experiences and approaches to disabilities come together, from distanced curiosity, through biographical and allied engagement, to a project of changing the world we live in. In late capitalist reality, disablement takes place on a global scale. Not only human and animal bodies are being exploited and harmed, but also the landscapes in which we live and which we are part of. The well-being of people with and without disabilities is therefore linked to the condition of the planet. As survivors on planet Earth, we must learn to live with the damage caused by the violence of capitalism, colonialism, and speciesism. This is the heritage we get from our ancestors. The ability to cope with it depends on situatedness. Politics of (In)Accessibility, Citizens with Disabilities, and Their Allies is a voice, or rather a polyphony of voices, in the discussion about what the category of disability is and could become, and how to use it to bring about a lasting change not only in the way we think, but also in the way our human-nonhuman communities and their institutions function.

By Zofia nierodzińska

[1] Sunaura Taylor, Beast of Burden. Animal and Disability Liberation, New York, 2017

[2] Extraordinary bodies is a term coined by American theorist Rosemarie Garland-Thomson in her book Extraordinary Bodies. Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature, Columbia University Press, NY, 1997

[3] Freak shows, i.e. exhibitions of people with unusual physical characteristics that were intended to shock the audience. From today’s perspective, freak shows are often regarded as socially-insensitive entertainment based on racism and ableism, and have rightly passed into history.

[4] https://www.dwutygodnik.com/artykul/7844-moje-niekoniecznosci.html (accessed: 7.12.2021)

![Rafał Urbacki, Mt 9,7 [On wstał i poszedł do domu]](https://arsenal.art.pl/content/uploads/2022/01/Polityka-niedostepnosci_dokumentacja_037-260x173.jpg)