Artists: Chór Czarownic/Witches Choir, Iwona Demko, Monika Drożyńska, Marta Frej, Irenka Kalicka, Kolaborantki, Kolektyw Złote Rączki, Zofia Kuligowska, Dawid Marszewski, Karolina Mełnicka, Ewa Partum, Liliana Piskorska, Jadwiga Sawicka, Ewa Świdzińska, Agata Zbylut

Curator: Izabela Kowalczyk

Fotoplastikon: Mateusz Budzisz, Barbara Sinica, Radosław Sto

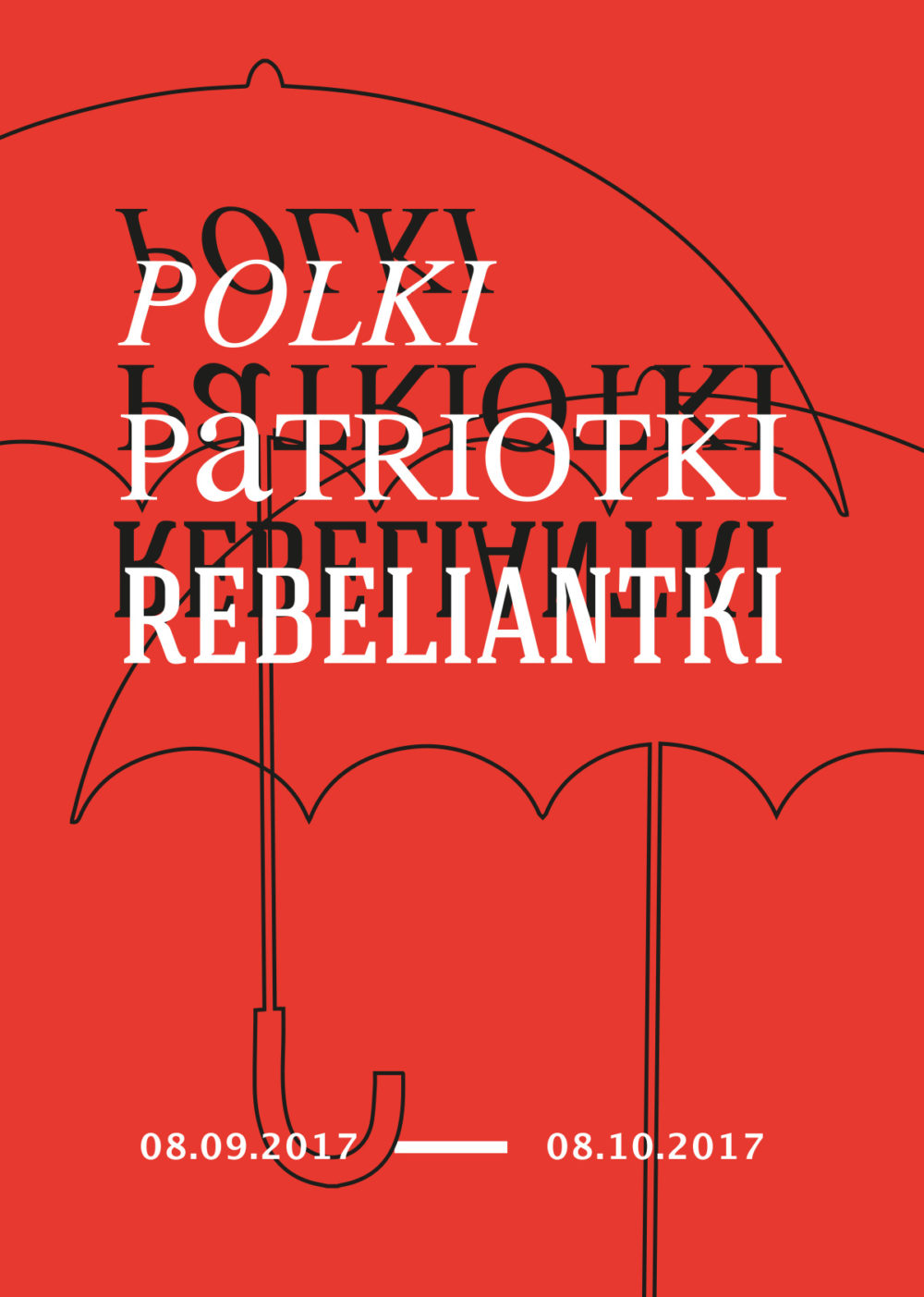

The exhibition Polish Women, Patriots, Rebels aims to reflect on the situation and problems faced today by Polish women – as citizens, participants in public life, patriots and protesters, When women’s issues are present in art exhibitions, it is most often in relation to what is private and personal, and they are rarely presented from the perspective of the public sphere. Meanwhile, if the topic of Polishness is taken up in art, issues related to women are generally considered marginal to it, as if Polishness and patriotism were exclusively male issues. The present exhibition seeks to change both of these optics by looking at women’s issues from the perspective of the public sphere, social protests, patriotism and civic engagement.

The impulse for organizing this exhibition was the events that took place during 2016, when plans to tighten Poland’s anti-abortion law were made public. This triggered a wave of protests unprecedented in scale (among these were In Our Cause on 9 April 2016, the Black Protest, and the Polish National Women’s Strike on October 3, 2016). These demonstrations brought together atheists and Catholics, anarchists and women belonging to various political parties, the wealthy and the poor, the parents of disabled children, single mothers, people involved in culture, students and a great number of other diverse individuals. These people were expressing their anger, and the massive scale of demonstrations across the country showed the government that it only takes a spark to ignite the masses. Women’s protests have also developed their own symbolism. Wire coat hangers wires and umbrellas have become their symbols (though the latter became so accidentally, due to the torrential rain that accompanied the October 10 protests, but failed to discourage women from taking part). Also symbolic is the wearing of black, which one can associate with the period of national mourning from 1861 to 1866. At that time, dressing in black dress was a manifestation of dissent against the policies of the partitioning powers and the bloody suppression of the Polish fight for independence. Today it has become a symbol of opposition to efforts aimed at depriving women of their right to control their own bodies. The strength of these protests stemmed largely from a collectivism that transcended divisions, best symbolised by images of a “sea of people” with umbrellas over their heads. This image can be read as a symbol of the rejection of one’s individuality and of uniting in a common cause – a symbol of collective rebellion against the unjust decisions of individual authority. This results in what Rosi Braidotti describes as “hybrid” social identities, indicating that these identities, as well as “the new modes of multiple belonging they enact may constitute the starting point for mutual respective accountability, and pave the way an ethical re-grounding of social participation and community building.”[1]

The current political battle over Poland’s future is largely taking place on the streets, and includes how both identity and community are understood (as closed and strictly defined, or as loose, fluid and open to others). The public sphere has become an arena for manifesting our values and opposition to those in power, a site of struggle over symbols, but also a space of repression and exclusion, eloquent and tragic demonstrations of which are the acts of violence against foreigners that have followed a wave of anti-immigrant phobia. The national symbols being used by the different parties involved are understood in different ways, as is patriotism itself (expressed through both nationalist-Catholic and critical versions). The visual forms associated with nationalist protests refer back to national traditions and the symbolism of power (including, not by chance, torches), but this expresses exclusively male power. A major role is played here by “football fan symbolism”, which alongside the symbols connected with the so-called “cursed soldiers” of the post-war anti-communist resistance, co-construct the iconography the struggle for an all-Polish “Great Poland”.

In contrast, women’s and anti-government protests use contemporary artistic strategies that emphasize less clearly-defined community action. During the Black Protests emphasis was placed on displaying female anger (women became menacing warriors with black stripes painted on their faces; they shouted about their strength; they made references to witches, pointing to the dangers associated with the modern-day symbolism of the stake and the pyre). It is through artistic, as well as musical, cooperative activity, which can be termed “feminist artivism”, that the modern feminism of power is built upon.

The exhibition is not aimed at rendering the atmosphere of the Polish street Anno Domini 2016 and 2017, but is instead intended as an artistic commentary on the surrounding reality and the situation of Polish women today.

Izabela Kowalczyk

[1] R. Braidotti, “Bio-power and necro-politics”. Published as “Biomacht und nekro-Politik” in Springerin 2/2007, pp. 18–23, available in English at: www.hum.uu.nl/medewerkers/r.braidotti/files/biopower.pdf