curator: Marek Wasilewski

The modern world is plagued by an excess of images. Each day, electronic media and social networking sites spit out millions of photos. The overwhelming majority of them are pictures depicting faces and scenes from people’s private lives. Visual culture researcher Nicholas Mirzoeff has noted: “Every two minutes, Americans alone take more photographs than were made in the entire nineteenth century […] By 2012, we were taking 380 billion photographs a year, nearly all digital. One trillion photographs were taken in 2014 […] All these photographs […] are our way of trying to see the world. We feel compelled to make images of it and share them with others as a key part of our effort to understand the changing world around us and our place within it.”[1]

Today we no longer ask ourselves whether photography is lying or how photography is lying. Theoreticians answered these questions back in the 1970s. The problem today is analyzing big data. Today we no longer ask about what we can see in a photograph, we ask what can be seen in a million photographs. Lev Manovich, the author of The Language of New Media, writes that instead of talking about a photograph as a single phenomenon, today we need to analyse photographic cultures. In his book Instagram and Contemporary Image he analyzes 16 million photos posted on Instagram in 17 global metropolises.

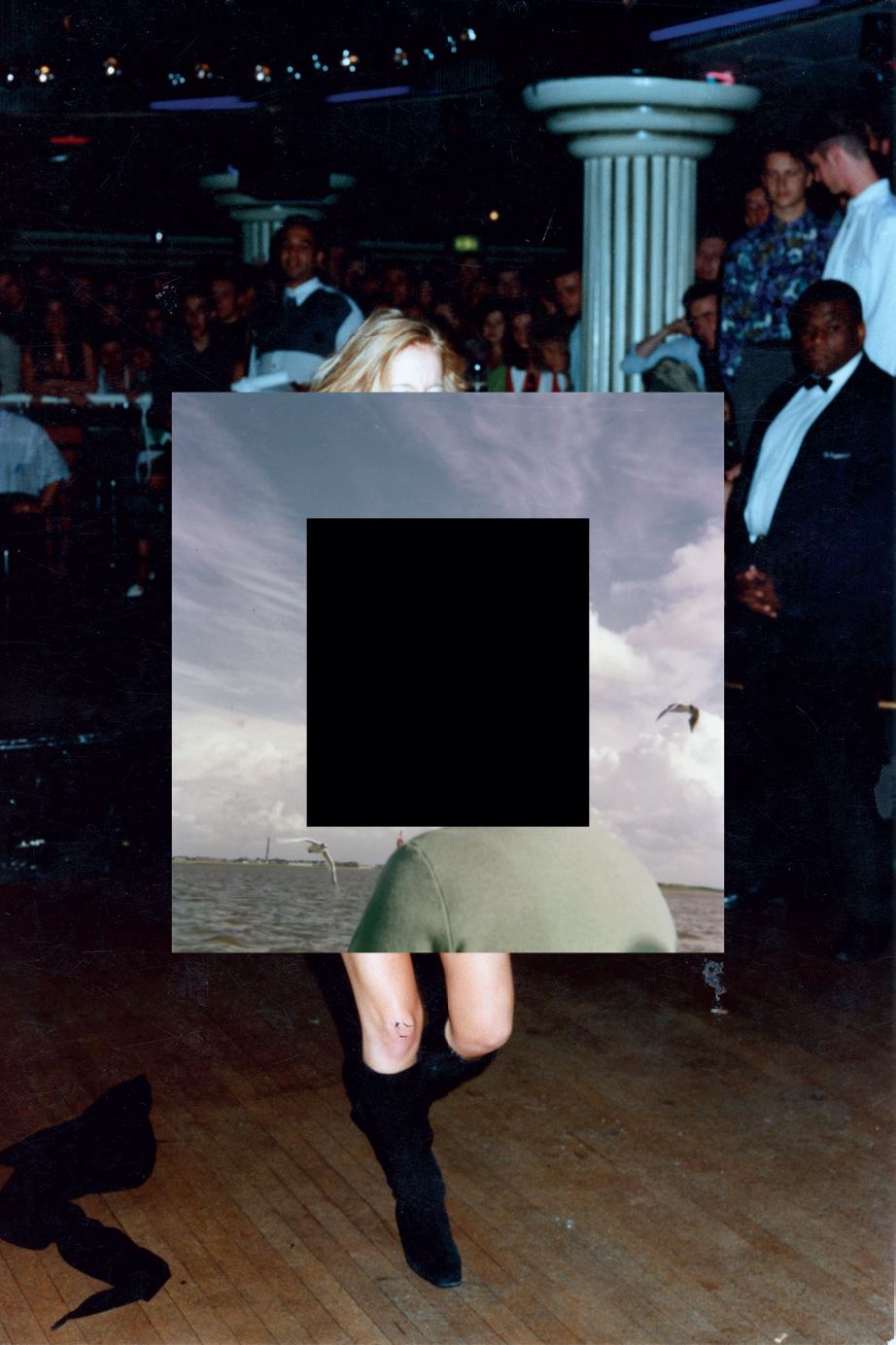

Maria Stożek and Adrian Kolarczyk’s exhibition relates to one of the photographic cultures defined by Manovich. The artists are intrigued by the collecting of analogue photographs, which can be purchased in Poland at open-air markets, as well as online. Unlike photographs seen online, these images also speak to us through their physical side. Their size, texture and colour, traces of wear, and accidental bumps and stains all have their significance. They mostly come from family archives that document life events, like holidays, car purchases, the birth of children, beloved pets and family get-togethers. They are part of a culture that developed after the Second World War, together with consumer society and the revolution in photography. The Kodak revolution, which grew out of the wide availability of cheap photo processing and printing through a vast network of photographic outlets, changed the photographic image just as profoundly, if not more so, than the emergence of social media in the early 21st century. Maria Stożek and Adrian Kolarczyk very quickly realized that in dealing with this phenomenon, they had to adopt the attitude of researchers who would not analyze individual photos, but instead study the correlations found in collections of them.

The artists write that: “(…) obvious analogies prompted us to develop systematic methods. The photos sold in open-air markets are remnants of family albums or depict events that were historically important. The divisions we used were based on certain key concepts, such as a motif, a sequences of images following one another (motion), a similarity in the positions assumed in a pose, a convergence between places, etc. Similarities between events led to the creation of further sub-categories, which gradually revealed a sociological dimension and led us to discover certain social values in the photographs. Different social groups make the same decisions when being photographed, which is then reflected in parallels in the aesthetics and manner of presentation of the photographed subject. New subsets result from the viewing of new situations characteristic of a given stage of life – young couples posing under weeping willows, photos on tree boughs, presentations of new equipment, sleep, cataclysms, or common events, like birthdays, holidays and funerals. We find pictures of people in windows, depicting trophies – fish, precious stones, televisions – and professional groups – nurses, nuns, priests, chimney sweeps.”

In their previous works, which have been shown both jointly and individually, Adrian Kolarczyk and Maria Stozek were interested primarily in revealing and exploring the internal mechanisms of systems of representation. A fragment of an infinite archive, as revealed by Stozek and Kolarczyk, might seem trivial at first sight. However, in the banality of this is an uncannyness that manifests itself in our perception of something that seems both well-known, and, at the same time, completely alien. The activity of looking at these photographs becomes just as controversial as the act of collecting them. We are not only confronted with questions about how the associative processes in our brain operate by means of visual cues, and how we are forced to organize everything we see, but, above all, we are left with the awkward question of why we are looking at these photographs in general.

Marek Wasilewski

[1] Mirzoeff, Nicholas. How to See the World. London: Pelican, 2015, p. 6.