The Art of Relations

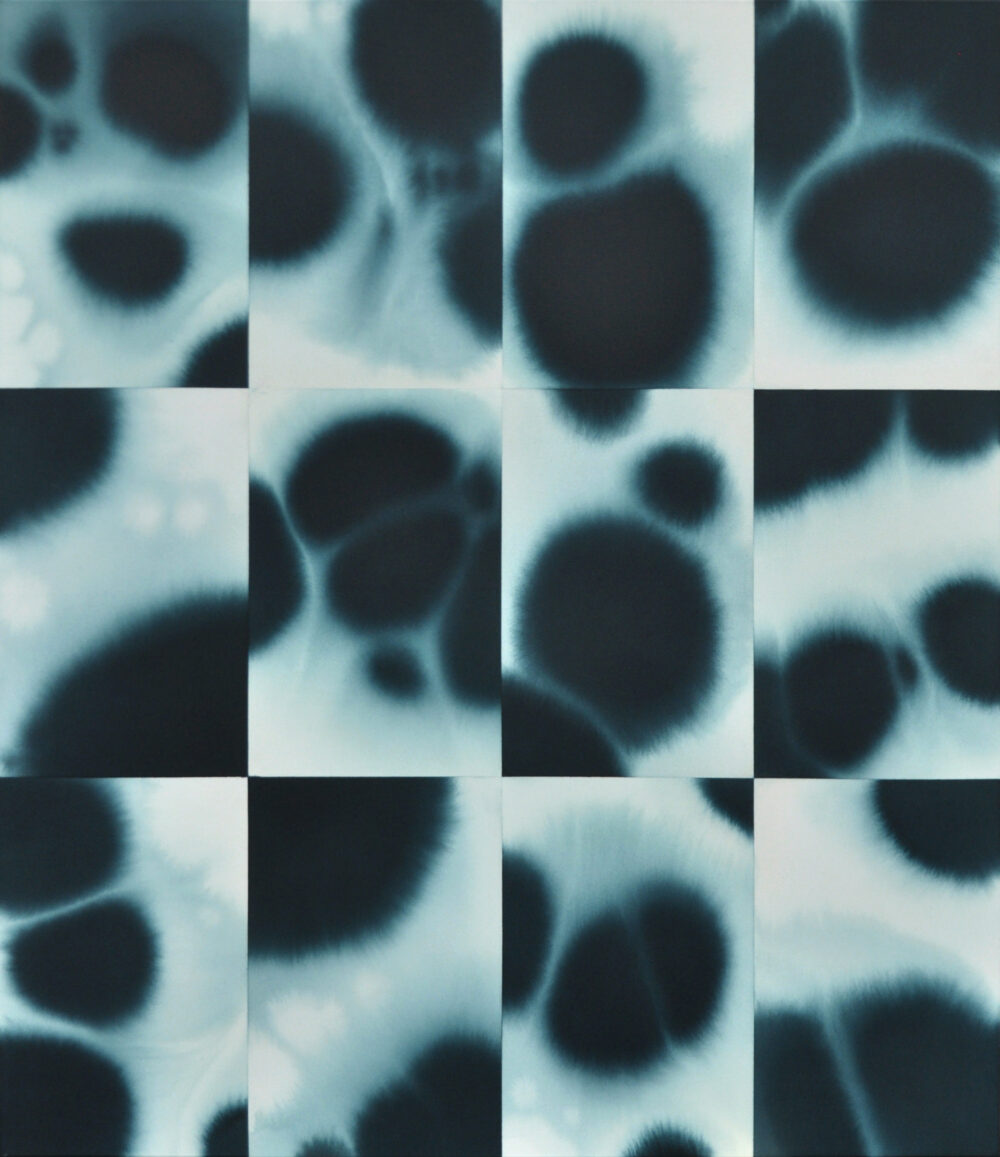

Małgorzata Szymankiewicz talks with Bogna Błażewicz on the eve of the exhibition Podzielone przez dzielenie / Divided by Sharing

Bogna Błażewicz: Let me ask you bluntly, as any visitor to the Arsenał Municipal Gallery can: what is divided by sharing at your exhibition?

Małgorzata Szymankiewicz: I see art, in this particular case painting, as an act of sharing an idea with the recipients. However, it can create divisions on multiple levels, e.g. in terms of interpretation, offering us the opportunity to differ in opinions, reception, and formal preferences. In addition, art can determine identity questions; via art we can identify ourselves with certain attitudes or ideas, or define our membership in groups or communities. Starting from the structural principles of a painting, which in my case consist in dividing a plane, composing it of smaller fragments or modules, or arranging the works in series, I should point out that a painting always has relational potential and becomes a space for multidimensional negotiation. The title of the exhibition can be understood in both a positive and negative sense, as a need for sharing which triggers proximity and community and an acknowledgement of diversity. However, it also points to existing divisions, inequalities, isolation, lack of dialogue, and exclusion of what is different.

BB: You have for years used and examined abstraction as a form of expression of a painter. You are interested in both arranging the strategies of imaging and the unique democracy of this kind of painting…

MSz: To my mind, the main and quite common mistake is to regard abstraction as form that invalidates any content. Abstraction, or non-figurative art in general, seems to me to be the most democratic, i.e. giving everyone a very similar chance from the outset, forcing them to receive sensually; there are no fixed patterns in this reception. Rather, one has to trust one’s senses and to surrender to the impression created in the relation to the art object. A painting is like an event for which we are never fully prepared, neither at the moment of creation or reception. A possibility of free interpretation is offered by the simple forms that abstraction usually employs or by paying attention to the basic means of painting. It is the potential diversity of these judgements and experiences that triggers a dialogue, an exchange of ideas, as well as a division. Besides, often the simplicity or minimalism of the painterly means is not the same as the simplicity of the message; the alphabet, too, being a set number of characters, offers a variety of often complex messages and meanings. I have found similar possibilities, demonstrating relationality in the broadest sense, in the montage strategies of imagery I researched when working on my doctorate, in postproduction, as well as in the esthetics of collage, which helps join opposites and which is based on the poetics of a fragment.

BB: You see abstract art first and foremost as an art of relations, as confirmed by your carefully crafted compositions. However, they are so precise and so formally detailed that a question arises whether relationships can be so perfectly controlled?

MSz: By no means! I have always viewed relations as very complex and unpredictable and that is why, to highlight opposites, I introduce an element of chance, organic forms, and freely spreading patches of paint having their own life, sometimes negating the discipline of compositional divisions or introducing a completely different order. My paintings try to merge contradictions, redefine boundaries and relationships between individual elements. Values such as geometricity/organicity, intentionality/accidentality begin to clash and collide. An optical illusion of motion and fluidity in a static image is full of meaning for me, too.

BB: I know you are now looking into the subject of an image as writing 2.0. Can you say something about it?

MSz: The concept of an image as a successor to writing, a form combining pictorial and linguistic potential, intrigues me. It sets a course of development for pictorialism, painting included. It shows the possibility of its transformation and marks its conceptual basis. Catherine Malabou or Vilém Flusser propose a view of the image that is similar in many respects, seeing it not as a passive reflection of reality, but as a dynamic communication tool encoding abstract concepts or constituting the source and depth of all discourse. While they have slightly different perspectives, as Malabou draws on the philosophy of neuroscience and Flusser more on photography and media theory, their concepts intertwine for me in a vision of the image as a new “alphabet” of complex meanings.

BB: What do you think a person not equipped with advanced art reception skills, one who has simply dropped by the gallery, might find for themselves in your exhibition?

MSz: I think every person has the competence and sensitivity to receive art. Often it is only our prejudices, preconceptions or conceptual clichés that are the biggest hurdles to perception, which this exhibition addresses, too.