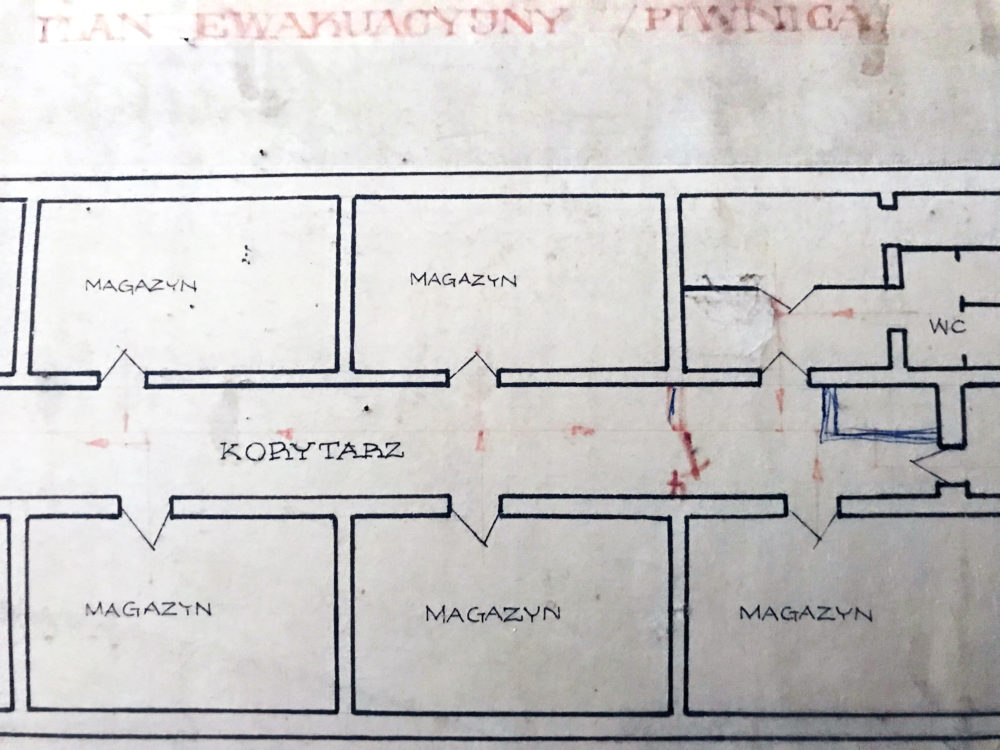

The Arsenał Cellars exhibition is an attempt at a critical evaluation of its collection. The eponymous cellars, a reference to Andre Gide’s famous novel The Vatican Cellars, are the storage space of the collection and the true protagonist of the show. The fantasy of the conspiracy theory described by Andre Gide spins an urban legend, repeated the world over, about a system of secret underground passages built under palaces and castles. Allegedly, the subterranean passages hide treasures, prisoners are subject to the cruellest of torture, but they are first and foremost escape routes. The collection of the Arsenał Municipal Gallery, started in the late 1960s, is stored in the basement under the gallery building. During the cold war period, the basement was used as an air-raid shelter by the residents of Poznań’s Old Town. Unearthing what is hidden, dormant and invisible, we take a stand with respect to what has been shoved into the institution’s subconscious. Bringing the contents of a cellar out into the open is like the social materialisation of the inherent ego of ghost-objects, which can be encountered solely in dreams. This psychological and archaeological activity is like unearthing the contents of tombs found in a desert, discovering secrets and shedding light on taboos. To a large extent, this is an activity that resembles a springtime cleaning up of a house, when we open our wardrobes and closets, airing their dusty interiors and taking out objects faded through a lack of interest in them. We regard them as if for the very first time, wondering why they have been unused for so long. The discoveries are accompanied by a feeling of curiosity, some unique tension characteristic of solitary trips into the unknown or into territories one has not ventured into for a long time. What can be hidden in the cellars of a city gallery? Who is the author of the Chucky painting? Did we have Polish Chapman brothers? What about the large-sized photographs left by a performer in 2004? How about this truncated sculpture, a torn-out hand, a wall hanging deconstructed by the biology of the passage of time, a painting cut in half to better fit the wall behind the desk in the secretary’s office? What about the archives of the Polish Sculptors’ Union? Or about pendants, copper medals, silkscreens, linocuts, and posters made for the print biennale …? Does anyone know their authors or owners? Can anyone put a price tag on them? Where and why should they be stored? What about the empty places that used to hold objects, whose presence is attested by inventory cards? What about those which arrived here without the requisite documents? Are they to stay here by virtue of “acquisitive prescription”?

We are intrigued by what is hidden in the closet, in the metaphorical “whale’s belly”, in what has been gathered in the whale’s entrails throughout its lifetime. An institution is like a whale that devours objects, documents and unidentified artefacts, willingly or otherwise. Most of the objects are digested and merge with the walls, seal tissues, cave in and seep under the floor’s surface, and are sometimes deliberately swept under a thick woollen abakan.

It is incredible, indeed, that a municipal institution of culture, in operation for a few decades, run by art historians, too, has never had a professionally managed collection of contemporary art, its holdings accumulating chaotically, without a plan and necessary discernment. At present, the contents of the Arsenał cellars resemble a fascinating and intriguing Wunderkammer, which imitates its historical original in that it groups a variety of diverse, loosely related items.

This unique cabinet of curios is an unwitting witness of its time, of a long marginalisation of the visual arts by all the successive political groups governing in Poland and a record of the history of the institution. The collection is moreover an account and metaphor of lost chances, wastefulness and the downplaying of the cultural and material legacy in Poland. In addition, it shows in an interesting way how the extant tangible objects, preserved from the past by a matter of chance only, does not in any way reflect the true image of its time; similarly, what is contained in the permanent form of sculpture, tapestry or painting is at odds with the comprehensive narrative of the avant-garde, the time of transformation, postmodernist assemblages, and fractal cyberspace. In their de-symbolised, physical presence, works of art can only constitute valuable arguments in contemporary discourses of new materialism, which – liberated from the language of signs – enters areas occupied so far by biology and physics. The Arsenał Cellars exhibition is intended to start a debate about what an art collection in the 21st century is and might be. Perhaps its tangible formula, seeking invariables in varnished canvases and concrete plinths, might be transformed so that, in a live transmission, it might more adequately reflect the nature of our fluid, ambivalent time, and change the artefacts of forgotten art works into interesting biotopes of all kinds of bacteria, fungi and protozoa.

Zofia nierodzińska, Marek Wasilewski